Just back from Hospital, after minor surgery. Concentrates the mind.

What the Sick Think

Beyond broad windows people tip home,

or back to work through the sluice

of traffic, rain, cold, or winter sun

brassy on their skin, but that is not for us.

Inside out like socks our focus is arcane,

the labyrinth of pulse and flesh and synapse,

inexplicably gridlocked. We are a breed apart.

The magazines and works of art,

the TV screens flickering in the evening

like bats, the crews landed here

to watch their beats and lifted off each

night, declare our exile. We read

our fate in those who pass exotically by,

gauzed and tubed, their faces closed

like blooms, We have only one question:

will things ever be the same for us?

Thursday, November 29, 2007

Thursday, November 22, 2007

Monday, November 19, 2007

Saturday Night

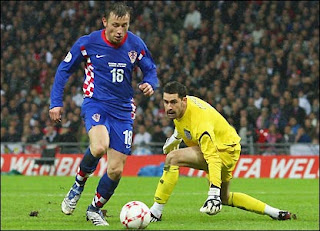

ach, the bitter dregs. I suppose having survived a two and a half hour wait in torrential rain during the early hours at Drumsleet's premier taxi rank I am lucky to be alive and reporting this sentiment. My mate in the queue decided to walk to Tesco's and sleep in the toilet there but I was made of stronger stuff and waited till half two in the morning, finally clambering aboard my taxi over the prone body of an old drab from Georgetown who had tried to nick it and had to be felled with a quick karate chop.

Why did we not have two men on the posts at that final, unjust free kick? Why did the mighty James McFadden miss what amounted to a sitter? The questions go on and on. A bizarre evening of sodium lighting, knackered trains, forced revelry and girls in tartan mini-skirts. And in the middle of it all the bold Andrew McMillan and Stuart Paterson, Scotland's most lost poet.

Well there's always England screwing up to look forward to. And the World Cup.

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

Remembrance Day 2

Lydia and I went to the wreath laying ceremony at Penpont, which is held just out the window. I wore my white poppy, Lydia her sticky red one. One of us carried a toy sheep but there was no symbolism in this. Trying to explain these things from scratch to someone with fierce intellect is difficult. I have great difficulties with remembrance day services and the concept of the glorious dead generally and specifically in the case of World War One. How anyone can continue to say that the soldiers of the Great War died for our "freedom" I don't know. If they died for any ideal (apart from the staggering personal courage some showed) maybe it's the glorious scepticism that in any civilised nation now surrounds concepts like patriotism and national duty.

Seems to me that the greatest, bleakest, poem about remembrance was written by a scot who died in the Great War.

When You See Millions of the Mouthless Dead

When you see millions of the mouthless dead

When you see millions of the mouthless dead

Across your dreams in pale battalions go,

Say not soft things as other men have said,

That you'll remember. For you need not so.

Give them not praise. For, deaf, how should they know

It is not curses heaped on each gashed head?

Nor tears. Their blind eyes see not your tears flow.

Nor honour. It is easy to be dead.

Say only this, "They are dead." Then add thereto,

"Yet many a better one has died before.

"Then, scanning all the o'ercrowded mass, should you

Perceive one face that you loved heretofore,

it is a spook. None wears the face you knew.

Great death has made all his for evermore.

Charles Hamilton Sorley

Friday, November 09, 2007

Remembrance Day

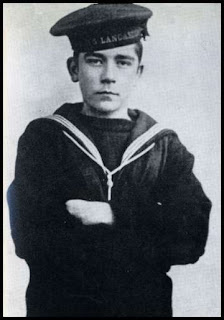

Just finished my part in a series of school assemblies on Remembrance Day. This years theme was boy soldiers and it was centred round the astonishing statistic that over 200,000 boys under the legal enlistment age fought in the British army during World War 1, about a quarter of its operational strength. The youngest was John Condon, killed aged 14.

Two youngsters were awarded the Victoria Cross, George Peachment and John Cornwell. The letter from John Cornwall's captain to his mother never fails to put a lump in the throat:

"He remained steady at his most exposed post at the gun, waiting for orders. His gun would not bear on the enemy ; all but two of the ten crew were killed or wounded, and he was the only one who was in such an exposed position. But he felt he might be needed, and, indeed, he might have been ; so he stayed there, standing and waiting, under heavy fire, with just his own brave heart and God's help to support him. I cannot express to you my admiration of the son you have lost from this world. No other comfort would I attempt to give to the mother of so brave a lad, but to assure her of what he was, and what he did, and what an example he gave."

Tuesday, November 06, 2007

It is always about this time of year that a tremendous hankering comes upon me to visit Mull and blether to my mother whose ashes we scattered near Pennyghael a long time ago. I don’t know why Mull has such a pull because though she was born there I associate and remember her more from Lochaline in Morvern, and when the pair of us used to go up north it’s there we headed for, as most of her own childhood memories and acquaintances were focused there. We used to rent a cottage from the Glasgow Morvern Association and walk through Kinlochaline and Ardtornish Estate to the castle on the point.

Since we were mostly poor we went the long way to get there- across the Ballachulish ferry, then across the Corran ferry on a gruesome single track road to Strontian then Lochaline. It was quicker but more expensive to go from Oban to Craignure, or Lochaline on the car ferry. At least I presume that’s why we always went the long way. Maybe there was another reason: a romance with small ferries maybe. Nowadays of course there’s a bridge at Ballachulish but the Corran Ferry is till there. Last time I tried to get there by that route was in the great year of madness- 1997?-when Eric Booth Moodiecliffe, (see below), who was driving, had a strange back spasm near Benderloch and we had to go home, via St Andrew’s and Hawick (don’t ask).

I think Mull is the target because I have my own layer of crazed memories now and also Mull has traditionally been a place visited as much in the mind as by the ferry. This year my pal Paterson and I intend to go to Mull to watch the Scotland Italy game. This is a proposition that in common with nearly all schemes involving Paterson, is impossible to achieve, or, at least, even if the gigantic logistical problems are overcome, has so many terrible consequences that it is hardly worth anyone of sensible mind contemplating. So that’s what we’re doing. Other completely impossible feats have been achieved in the past, after all. I need only think of the Dumfries to Tobermory on a fiver expedition which involved a landslide, a 22 mile walk in the middle of the night, a riotous night at Ian Crichton Smith’s house and the Taynuilt Highland Games.

Since we were mostly poor we went the long way to get there- across the Ballachulish ferry, then across the Corran ferry on a gruesome single track road to Strontian then Lochaline. It was quicker but more expensive to go from Oban to Craignure, or Lochaline on the car ferry. At least I presume that’s why we always went the long way. Maybe there was another reason: a romance with small ferries maybe. Nowadays of course there’s a bridge at Ballachulish but the Corran Ferry is till there. Last time I tried to get there by that route was in the great year of madness- 1997?-when Eric Booth Moodiecliffe, (see below), who was driving, had a strange back spasm near Benderloch and we had to go home, via St Andrew’s and Hawick (don’t ask).

I think Mull is the target because I have my own layer of crazed memories now and also Mull has traditionally been a place visited as much in the mind as by the ferry. This year my pal Paterson and I intend to go to Mull to watch the Scotland Italy game. This is a proposition that in common with nearly all schemes involving Paterson, is impossible to achieve, or, at least, even if the gigantic logistical problems are overcome, has so many terrible consequences that it is hardly worth anyone of sensible mind contemplating. So that’s what we’re doing. Other completely impossible feats have been achieved in the past, after all. I need only think of the Dumfries to Tobermory on a fiver expedition which involved a landslide, a 22 mile walk in the middle of the night, a riotous night at Ian Crichton Smith’s house and the Taynuilt Highland Games.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)